The American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD) describes physical fitness as a physical state of well-being that allows individuals to perform routine activities without vigor, and reduce the health problems associated with a sedentary lifestyle (1). Moreover, the American College of Sports Medicine considers physical fitness to be a multifactoral construct consisting of cardiorespiratory endurance, body composition, muscular strength and endurance, and flexibility (2).

Several reference standards have been established for

assessing the specific components of physical fitness (3). The Sit-and-Reach

test (SRT) and the new Back Saver Sit-and-Reach test (BSRT) used in the

Prudential FITNESSGRAM and the AAHPERD's Physical Best test are examples

of popular flexibility tests currently using Criterion and Normative Reference

Standards (CRS) (2, 4). These tests are used by exercise physiologists and

physical educators to measure low back and hamstring flexibility (5). Proponents

of the Physical Best, and the FITNESSGRAM's Sit-and-Reach tests, hold that

these standards of measurement provide an easy to use, immediate, indication

of the minimum level of physical fitness needed for good health and daily

functioning (4). However, the validity of the SRT and the BSRT has been

questioned. For example, previous research on the SRT and the newly implemented

BSRT, has produced results that implied only a low to moderate amount of

validity in assessing lumbar extensor and hamstring flexibility (5, 6, 7).

The SRT and BSRT's lack of validity may be partly contributed to anthropometric factors, such as the disproportionate length of the limbs relative to the trunk which is often associated with the growth spurts of children (8, 9). Furthermore, in some instances, one muscle group may overcompensate for the lack of flexibility in the other group, resulting in misclassification of the child's range of motion (9).

In such instances, exercise physiologists and physical educators might find a Norm Referenced test that assesses the hamstring musculature separately to be useful when testing the flexibility component of physical fitness. A recent literature search, however, revealed little information as to how to perform such a test correctly. Therefore, the purpose of this paper, is to present the Passive Straight Leg Raise Test (PSLRT).

Equipment

In order for the exercise physiologist to perform the passive straight leg raise or active lumbar flexion test a standard (36" height) examination plinth or exercise mat and goniometer are required. A goniometer is plastic instrument designed to measure the range of motion of a joint in one-degree increments up to 180 or 360 degrees. The basic design of a goniometer is that of a protractor to which two movement arms are attached. One arm remains stationary, and the other is designed to move about the fulcrum of the goniometer (10). Proper use of the goniometer for the aforementioned tests will now be described in detail.

Passive Straight Leg Raise Test

The Passive Straight Leg Raise (PSLRT) test requires two test administrators skilled in goniometric testing. For the purpose of this article the administrators will be referred to as test administrator one and test administrator two.

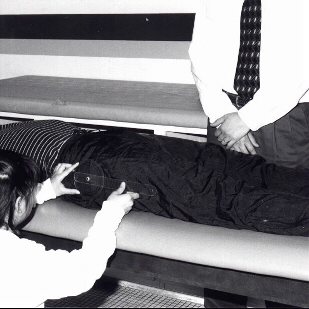

The Passive Straight Leg Raise Test begins by instructing

the client to lie in the supine position on an examination plinth or exercise

mat. Test administrator one places the goniometer's axis over the greater

trochanter of the femur (three to four inches from the mid-iliac crest) of

the left hip. The goniometer's stationary arm is placed over the lateral

aspect of the mid-thoracic region of the rib cage. The movement arm is placed

over the lateral aspect of the femur's shaft (see figure I).

Figure I: Goniometer placement during the Passive Straight Leg Raise Test (PSLRT)

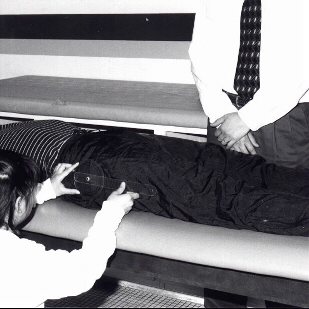

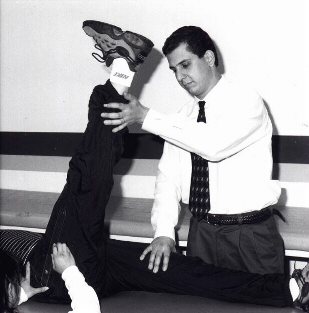

With the goniometer in this position, the second test administrator places his right hand just superior to the proximal aspect of the right patella. Next, the administrator grasps the posterior aspect of the medial portion of the client's right calf with his left hand. The test administrator passively raises the right leg with his left hand while keeping the clients knee extended at 0 degrees and ankle dorsi flexed to 90 degrees (see figure II).

Figure II: Passive flexion and goniometer measurement of the hip joint during

the

Passive Straight Leg Raise Test (PSLRT)

The tested limb is raised by test administrator two until muscular tendinous tension is elicited in the hamstring and calf musculature, or there is an increase in posterior pelvic rotation (8). Goniometric measurement is taken by test administrator one at this definitive point of hip flexion. The norm referenced criterion measurement for adequate hamstring flexibility is 70 degrees of hip flexion with posterior pelvic rotation permitting 10 degrees of pelvic tilt (8).

Conclusion

Many exercise physiologists and physical educators currently utilize the Sit-and-Reach Test and Back Saver Sit-and-Reach Test for assessing the flexibility component of physical fitness. Research indicates that these tests only have a low to moderate amount of validity. The SRT and BSRT's lack of validity may be partly contributed to the test's inability to separate the hamstring from the lumbar extensor musculature during testing. This limitation can negatively impact the assessment of specialized populations, such as children experiencing the anthropometic factors associated with a growth spurt.

In contrast, the norm referenced Passive Straight Leg Raise Test, described previously, allows the test administrator to assess the hamstring separately from the lumbar extensor musculature. It is anticipated that this test will provide exercise physiologists and physical educators with a reliable alternative to the Sit-and-Reach Test when assessing the hamstring flexibility.

References

1 Auxter D, Pyfer J, and Huettig C. Principles and Methods of Adapted Physical Education and Recreation. 8th ed. St Louis MO: Mosby Year Book, Inc, 1993.

2 American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 5th ed. Media PA:Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

3 Lavay, B. Guidelines for Testing The Physical Best and Individuals with Disabilities: A Handbook for Inclusion in Fitness Programs. Reston VA:AAHPERD, 1995.

4 Cureton K and Warren G. Criterion-Referenced Standards for Youth Health-Related Fitness Tests: A Tutorial. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 61:7-19, 1990.

5 Patterson P, Wiksten D, Ray L, et al. The Validity and Reliability of the Back Saver Sit-and-Reach Test in Middle School Girls and Boys. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 67:448-451, 1996.

6 Jackson B and Baker A. The Relationship of the Sit-and-Reach Test to Criterion Measures of Hamstring and Back Flexibility in Young Females. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 57:183-186, 1986.

7 Jackson B and Langford N. The Criterion Related Validity of the Sit-and-Reach Test: Replication and Extension of Previous Findings. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 60:384-387, 1989.

8 Kendall FP and Kendhall EM. Muscles: Testing and Function. 3rd ed. Baltimore MD:Williams & Wilkins, 1983.

9 Roncarati A. Is an Alternative to the Sit and Reach Test Necessary? Selected Readings in Sports Medicine. Dubuque IA:Brown & Benchmark Pub, 1997.

10 Daniels L and Worthingham C. Muscle Testing. 5th ed. Philidelphia: WB Saunders Company, 1990.